The Conscious Traveler: Peru

In The Beginning

It felt like I had walked for days to get to the first town after passing the border from Ecuador to Chile. By dusk, I had finally been able to catch a taxi passing by to drop me off in the most northern city in Peru, Piura. What I had planned to be only one night passing through to “Cascada La Novia” ended up being a month of teaching Muay Thai and English, having an opportunity to read and write, and trying to take care of some much-needed business. Percy was the name of my English student. He lived in this hotel with his mother, whom she and her sort of estranged husband owned.

The border of Peru and Ecuador

I could fill an entire article about my time with the family. Percy was one of those too-smart-for-his-own-good type of kids, and his mother was one of those too-kind-for-their-own-good type of women. His father never cared to interact with me much. I think it had to do with the deal the three of us made where I would teach Percy English while staying in the hotel. Also, Percy and I were always up to shenanigans, like the time I brought back a stray kitten to the hotel, and Percy and I searched for a home for the little fella through the night.

Me and Percy in the middle of saving a stray cat

I also had the opportunity to train at a decent gym. Piura Muay Thai was a good place to stay on top of my training, although the days were not what I had hoped they would be. The gym was only open three days a week, and personally, I find it hard to keep up with a good gym regime going less than five days a week. With that said, though, I do find the fight team there to be pretty good. Although they are predominantly mixed martial artists, I find their striking to be quite decent.

At a different gym, I found the opportunity to teach Muay Thai as well; I had a lot of time on my hands. I had a couple of regulars and guys I turned to the gym I was training at. It felt a bit like repeating what I did in Nicaragua, but only for a short-lived time. After my month in Piura, I was off to California for two weeks, where I presented my mother’s documentary.

A couple of the local kids I was training

Return To The US

Here is where things became a little spotty for me. So many mixed emotions and swells of aggravation came out of my time in California—things that I am still put off by today. Not only for what was going on there but for so many things dealing with the legacy of my mother. On the bright side, I had the chance to meet so many of my mother’s fans, head to the Bay which I consider a second home away from New York, meet Jacquie from Black Stack, and catch up with old friends. Thank you, Meg, for letting me crash on your couch.

Outside the theater NuArt Theater in L.A.

The Andes and Cascada La Novia

Coming back to Peru, things were in full swing. I was ready to get everything done this time around that I had planned on the month prior. Plus, I had just published my best work yet, “anti black pro black, black people.” So I wasn’t pressed to get any work done. Heading out of Lima proved easier than heading to my destinations starting in Piura anyway.

The first stop was Cascada La Novia. I took the overnight bus to Cajamarca, where I finagled my way onto a “mini bus” to what I thought was the town of Micuypamp, but upon arrival, it turned out I was in the town of Celendine. In the morning, I told the bus driver he had dropped me off in the wrong area, and after getting on the bus heading back to Cajamarca, I let him know he had once again missed my town. So I hopped out of the van in the middle of the Andes Mountains and hitched my way back to the town. A young man and two women, Jonathan, Tatiana, and Talia, drove by and stopped. I told them where I was going, and they escorted me there. When I walked down the dirt road into the very, very small village, Jonathan’s van followed. I said, “You live here?” He replied, “Yes, and you are just in time; the village is having a party tonight.” I was excited. The villagers brought me to the hut where they had been cooking dinner for themselves and extended family from the region who would be joining them. The village on its own houses about sixty or fewer people, but this evening there were a whopping one hundred fifty people there. After dinner, I helped clean up, and we headed to the church they had built in the middle of the village. Okay, I thought to myself, “Nothing wrong with a little prayer before a party.” Little did I know, this was the party. We were in church for seven hours, and around two in the morning is when they realized your boy could not hang, and they showed me to my bed, a four-foot mattress on a bundle of logs. They gave me plenty of blankets and a poncho to keep warm in the freezing Andes temperatures. After an hour of sleep, one of the elder women, Esmeralda, escorted me to better accommodation in the church made up of two pews put together.

Eating potatoes and hot coco ft. Okami

In the morning, I woke up and was adamant about getting to the cascade. Roughly understanding the hike will be five to six hours one way, I asked one of the village leaders what his estimate on time was. He told me one and a half hours. With my skepticism, I started to walk. After an hour and a half, I had barely reached the entrance to go to the cascade. Luckily, I was able to hitchhike with this truck driver delivering some sort of construction material to a remote area, probably to start a building project that will never get finished—plenty of that here in Latin America.

Cascada La Novia

At the cascade, a group of teenagers were playing around the rushing water and jumping from rock to rock, but two of them were stuck, and their friends simply left them there to figure it out. The first boy jumped, falling into the water without a friend to help. He was able to pull himself up, though, before being pulled down the rocks by the rushing water. He did not even look back to help his friend out; instead, he left him behind. I yelled to get the children’s attention to let them know the other boy would need help as well, but no one helped. So I rushed down to where he was, jumping halfway across the rocks to give a helping hand. He tossed his belongings, which I tossed to the mainland, and then he jumped, completely missing the landing and my arm; he fell into the water. I got into a prone position to drag him out of the water by his belt strap, only for him to jump ahead of me without even uttering “gracias.” Actually, not a single one of them said anything to me for helping their friend. I was happy to have saved him, but part of me wishes I would have let him suffer a bit.

Paracas

I left the Andes the following day and headed south to Playa Rojo. It proved a bit difficult for me to get to. I got to the little highway town of Santa Cruz, where I could not find accommodation, so I walked through the night down the road towards Paracas, finally finding a hotel for the evening. When I awoke in the morning, I found myself in the desert, a real and complete desert. With no modes of transportation in sight, my dog Okami and I finished the three-hour journey through the desert sun with our packs on our backs, making it to the first beach I had seen since leaving the diving school in Honduras.

Met an Ecuadorian merchant named Jaguar, selling souvenirs on the beach with her baby

I was able to find a nice beachfront hotel for about twenty bucks a night and made friends with some Ecuadorian folks and their little one-year-old baby, who had several swigs of beer in my time around him alone, hanging out on the beach for the season selling merchandise to tourists. In the morning, Okami and I made our trek through the rest of the Paracas Peninsula through the desert to Playa Rojo. This possibly being the most surreal experience I have had in all my years of travel. I never thought, prior to that conscious choice I made in Colombia to see more nature on my journey around the world, I would ever be walking eight to ten hours through a desert.

Playa Rojo

It All Works Out In The End

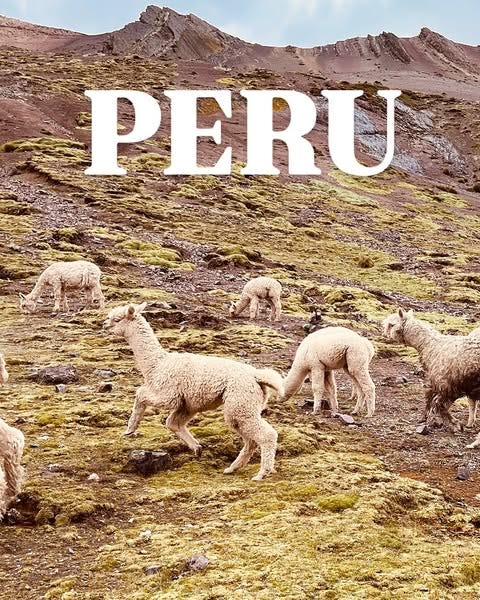

I left Paracas in hopes of going to Machu Picchu, but in my attempt to get there, I kind of lost interest. I was feeling complete in Peru, and I didn’t really care to see the most popular monument in the country, knowing it would be overburdened with tourists. I was already tired of seeing the ones I saw in Paracas, also the most I have seen since leaving Honduras. I opted instead to see the lesser-traveled location, the Rainbow Mountain, Vinnicunca, and for thirty dollars, it was the icing on the cake I needed for Peru. This is not the only rainbow mountain in the world; China has one, and any area on Earth that has different conglomerates of rock types can have this effect. What makes Vinnicunca special is that on all opposing sides of the mountain, there is a different type of biome. Once again being back in the Andes, I was only feet away from the snowcaps. In the area I was in was a lush green valley. On the other side of the mountain, a deep marigold yellow plain. Hike only twenty minutes more, and you are in Valle Rojo, a place so deeply red it looks like a package of strawberry chewing gum with vegetation growing from it. For the amount of not-so-popular but definitely magnificent and dare I say world-wonderesque nature I had seen in those three weeks, I felt accomplished, and for the ways I moved around Peru, I felt like I had finally been getting into this next chapter of the conscious traveler.

Mount Vinnicunca

On a different note: I have been neglecting my more critical analysis of the most recent countries I have been in here in South America. Because of this, I wanted to give a slightly more detailed analysis of some of the issues I have seen here in Peru. Not to turn this into an uninformed hit piece on Peru, I decided to consult a fellow writer and Lima local, Ines, who writes the newsletter “The Cranky Guide”. Recently, she wrote a piece highlighting the similarities between Latin American dictators and the United States' current administration. I knew she would be a good person to talk to, to help me understand what I experienced here.

Upon entering Peru, it was clear that out of the entirety of countries I have been to in South America, Peru had the highest amount of policing, militarism, hyper-surveillance, and praise for big brother. Safety is subjective when talked about in a non-present tense, and depending on whom you ask, one country is considered safe, ask another, and it would be considered Mad Max Fury Road, but Peru for the most part is deemed as unquestionably safer than its neighboring countries to the north. Yet, Peru has the largest presence of big brother I have seen since leaving Honduras. I asked Ines why she thinks this is the case:

“- High influx of petty crime (led to) people trying to feel safe. There was a lot of petty crime, but not necessarily a large influx of violent crime, (but recently) there have been a (growing amount) of violent crimes. Extortion of store owners and not really (just) the rich, (but of everyday common people).”

She followed this up by saying,

“The state has ignored this part because it affected poor people, but the issue has grown so large that the police have been forced to take action, but most of this is for show. The police are badly trained and also underfunded. (On the other hand) if bad people are caught, the corruption in the justice system will let them walk, or because of the overpopulation of the jails, offenders are often in there with other gang members (cooperating on more crime).”

From my own analysis, I have seen the militarization of students and the abundance of military academies throughout the entire country that starts students out on the pipeline of becoming part of the police force or military. This has led to an extremely young police force that, from what Ines has told me and from my own experience, is extremely incompetent and cannot solve any of the problems “crime” has brought to Peru. Yet, the force is beloved and praised by the Peruvian people, and in many areas, Peruvians have given up autonomy to feel safe rather than be safe. Now, this is not only an issue here in Peru. I have talked in the past how in many Latin American countries, entire towns and cities of people have given up much of their privacy and agency to big brother (police, military, and business surveillance), not only to “feel” safe but because they feel they deserve this access to protection that is, in their minds, similar to the United States and many European countries. There is this idea, especially as I am here in the Global South, that access to certain luxuries—if they be luxuries at all; often times, they are just inconveniences (gated communities in Central American cities)—are needed here to feel on par with the White West. You add a constant route of migrants from Venezuela and Colombia passing through here and the Peruvian/Chilean xenophobia towards that said group, and you have created a racist, prejudiced system of policing and surveillance that is absolutely on par with the United States and any other country on paper. Take the young men who have been groomed their entire life to be part of the policing mob and not think for themselves, and you have a similar issue to what you have in Honduras: an entire police force of incompetent young men led by a small batch of old men who just don’t give a damn. Mix it all together, and you have a problem on your hands, Peru—something that, if not dealt with, may end up imploding on itself.

I will be talking more in-depth about the topic of the intersection of migrant travel and policing here in Peru and Chile in my article about Chile. Currently, I find myself living in and out of a Peruvian refugee and migrant camp on the border of Chile. This piece hopefully will be coming out soon after my piece on Bolivia, where while walking through the desert, I questioned my own sanity and had a conversation with God. Love you all❤️, Peace.